The Specular Interiors of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century France

Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors) in the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France.

““Man is mirror for man. The mirror itself is the instrument of a universal magic that changes things into a spectacle, spectacles into things, myself into another, and another into myself. Artists have often mused upon mirrors because beneath this ‘mechanical trick,’ they recognized, just as they did in the case of the trick of perspective, the metamorphosis of seeing and seen which defines, both our flesh and the painter’s vocation.”[1]”

The mirror is a human-made object. It is not a found natural material like marble, limestone, or onyx. It is a product of human science and inventiveness, composed of a pane of flat glass with a coat of melted minerals on one side of the plane.

The present-day perfection of the looking glass took centuries of development to achieve. To obtain a pristine reflected image, a clear high-quality glass is necessary, and the contemporary quality of manufacturing is an accomplishment that took much effort to reach. As Sabine Melchior-Bonnet states, “the composition of the glass itself changed little over the centuries, even if the precise role of each element in the formula—silica, sodium oxide, and lime—was not entirely understood (lime’s action on the process was not fully identified until the middle of the eighteenth century). The quality of the glass was improved gradually through trial and error by varying the proportions of the ingredients.”[2] Moreover, the manufacturing of mirrors demanded the development of clear glass without the presence of bubbles, which distort the mirrored reflection. Additionally, the production of glass needed to reach a point where flat cast glass could be manufactured, and these panes of glass needed to be back-painted with the right material to produce a perfect reflection. Finally, these panes of glass needed to be produced in large sizes, a development introduced by French innovation in the late seventeenth century.

This progression of events took place over several centuries and at the center of these developments is a remarkable period in the history of the decorative arts in France, roughly between 1650 and 1850, a period in which mirrors turned from an oddity to one of the most sought-after and valued pieces in interiors. It begins with Louis XIV, under whose reign one of the most exceptional achievements in the history of interior design was accomplished: The Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles. In this gallery, mirrors were used innovatively—and extensively—for the first time as a finish in architectural interiors. After that, mirrors were further incorporated as a wall finish in various fashions and were also introduced into pieces of furniture for self-grooming, or as horizontal or vertical finish on furniture themselves. Additionally, they were developed as stand-alone full body mirrors, also called “Psyché,” a mainly French invention.

This essay argues that in France and globally, this period in France is pivotal to understanding the use of mirrors as an architectural finish from that period and onward, tracing the most important aspects of the history of mirrors in France during the period between Louis XIV and Napoleon’s tenure. It will cover a brief history of mirrors, how the Hall of Mirrors came into being, highlights of French mirror technological advancements, the lineage of important architects in France whose work influenced the field throughout Europe and beyond, and it will address its further applications in interior architecture.

A Brief History of the Mirror

People probably first started to look at their reflections in ponds of water, lakes, and rivers or even on the surface of water contained in vessels: these were the first natural mirrors available. Originally, mirrors were relatively small and very expensive, and they remained so for millennia. The earliest human-made mirrors were polished stones made from black volcanic glass obsidian—a chemical composition with high silica content, which at high temperature and upon swift cooling, forms a natural glass from the lava. Later, the ancient Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks could manufacture mirrors from polished copper and bronze.

Mirrors remained small for many centuries. In Europe, the invention of glassblowing and its application to making mirrors, happened during the fourteenth century, and following this, the use of mirrors became more widespread in the late Middle Ages. Small convex ones appeared and can be seen in paintings as a testimony of their existence. Their use was more as a decorative element than a practical one. However, in the sixteenth century, small handheld mirrors of polished steel or tin useful for seeing one’s own face became widely available and were sold at fairs by street vendors.

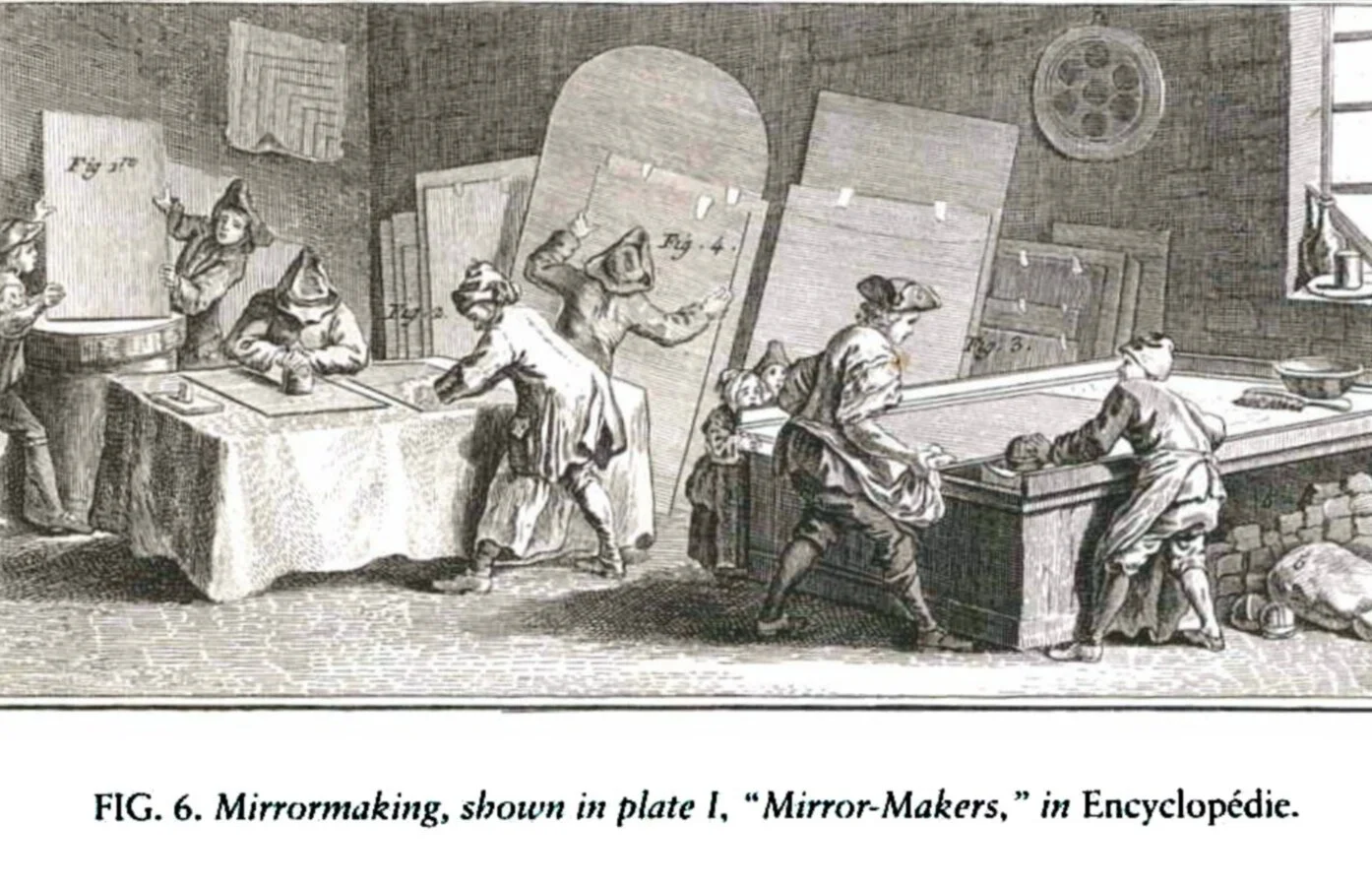

In the sixteenth century, Venice became a center of mirror manufacturing, using a new technique of coating glass with a tin-mercury amalgam, producing better reflectivity than the crystalline metals used previously. In the middle of the seventeenth century, mirrors began to be used to double the apparent size of rooms. By setting many small pieces within paneling, Venetians began making more significant mirror assemblies, which were used by the wealthy to create mirrored rooms. Until then, mirrors made in Venice measured only about twenty-eight inches high.[3] However, their glassmakers had been able to produce “crystallo” glass, a type of glass with a clarity that no other region in Europe had been able to achieve. Hence, they were able to manufacture the highest quality type of mirrors and glass products from the island of Murano in Venice, which were greatly valued in Europe.

Venice was the center of production and technological advances regarding mirror manufacturing until the middle of the seventeenth century, but after that, it was in France that the creative application of mirrors in interior architecture and the decorative arts was further developed as a universal lexicon. These innovative applications of mirrors in interiors prompted the interest of French manufacturing into technological progress, posing a real competitive threat to Venetian production.

At the beginning of this shift, around 1665, France alone imported yearly around 100,000 crowns worth of mirrors from Italy. The French market was searching for mirror products that the many small glassmakers in France could not provide. First, they could not yet achieve the clarity and transparency of the Murano glass. Second, they did not have the technology to apply the right type of back coating as in Venice. And third, they did not yet know how to produce glass casting to obtain the flat surface necessary to achieve an accurate reflection. The Spaniards, the Germans, and the British were also struggling to produce a breakthrough in technology with no substantial advancements. Only Venice had the secrets of “crystallo” glass and mirror making, which the aristocratic class in Europe so dearly sought. Mirrors were signs of supreme luxury, and Venice had its monopoly and was determined to keep its technology for itself.

In the meantime, in France, many small glassmakers were fighting to improve their production and reach a level of competitiveness with the Italian mirror makers to no avail. Instead of continuing to support non-competitive and precarious glassmakers indefinitely, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the minister of finance of Louis XIV, canceled all manufacturing privileges previously granted to them, and in 1665 sought to initiate economic reforms. Among similar measures being applied to other areas of craftsmanship, he ordered the establishment of a state enterprise creating a royal manufacturer of glass and mirrors. It was named the Manufacture des Glaces and was located in the suburb of Saint-Antoine, in Paris, an endeavor that would greatly expand the production of mirrors in the country. Colbert managed to import Venetian glassworkers who were put to work alongside French glassmakers.

Concurrently, while the French were desperately trying to steal their secrets, the Venetians were furiously implementing all kinds of measures to preserve their secrets for glass and mirror making. Colbert’s initiatives triggered a series of altercations and struggles between Venice and Paris, roughly between 1660 and 1700, resulting in many dramatic events including schemes, human contraband, and even death among Italian glassworkers.[4] Many years passed before the Manufacture des Glaces began to show evidence of some success.

The Hall of Mirrors

Simultaneously, the Chateau de Versailles was subject to renovations, and in 1678 “The Hall of Mirrors” was to be designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart. His participation in the renovation came about when the king had requested the design of a gallery in place of a terrace overlooking the gardens. The acceptance of Mansart’s design was directly related to his flexibility in accommodating a painted ceiling to be realized by Charles Le Brun, the imperial painter, since this feature of the gallery was the primary concern of the Roi Soleil. The ceiling would be painted with the representation of the history and triumphs of the king, and the central focus of the architectural program was to provide the broadest possible ceiling surface for the paintings with an elegant proportion to handsomely frame the preeminence of the monarch in pictorial form.

Mansart was granted the approval of his project on 26 September 1678, designing the exterior enclosing walls as well as its interiors, extending the terrace by eliminating two large rooms of the new apartments of the King and the Queen (each located at both ends of the terrace), and making it high enough to occupy two floors upwards. The gallery was massive, measuring 73 meters long (approx. 240′), 10.50 meters wide (approx. 35′), and 12.30 meters high (approx. 40′).[5]

However, Mansart’s scheme had a severe problem: the lack of interior illumination for the ceiling of the gallery. After some more creative iterations, in 1679 Jules Hardouin-Mansart devised an idea that would forever inscribe him in the history of the decorative arts: the extensive use of mirrors on the walls opposite to the windows of the gallery. In this way, the mirrors were also advanced as a material infused with meanings and connotations that resonated splendidly with the iconography devised to highlight the Roi Soleil. As Joyce Lowrie writes, “The Sun King wished to reflect and magnify his power and his glory into infinity, and the lavish use of mirrors helped him do just that.”[6]

Mansart’s further development of the interior of the gallery included a new French capital for the pilasters along the east and west sides of the gallery, and most importantly, the extension of all windows on the west wall to the floor, to provide the hall with maximum brightness. The shape of the windows was also altered with a semicircular top, instead of the original rectangular form. That was the birth of what is called today the “French window.” This window design accentuated the gallery’s ancient Roman iconographic association, and conceptually connected this architectural feature with the exterior of the Coliseum. Additionally, the sense of order and symmetry was underlined with the placing of mirror areas on the interior walls as precise reflections of the windows on its opposite interior side, with their same size and shape. The grand hall was designed with seventeen mirror-clad arches, encompassing three hundred fifty-seven mirrors, reflecting seventeen opposing arcade windows.[7] The mirrors are surrounded by marble cladding, added in 1679 and bronze gilt ornaments with classical motifs figuring prominently at the dado height, the cornices, and ceiling levels, encasing the vault with its thirty paintings done by Charles Le Brun, which were realized between 1681 and 1684. Additionally, sculptures were put into place in 1680.

The original furniture devised for the gallery included chandeliers, candelabras and console tables of pure silver. In 1687 Nicodemus Tessin, a Swedish Baroque architect visiting Versailles counted one hundred sixty-seven artifacts of solid silver pieces of furniture in the state apartments, of which seventy-six were placed in the Hall of Mirrors.[8] The final result was a gleaming environment with rays of light coming from the sun and projected on mirrors, silver furniture, and gilded finishes to the astonishment of its admirers. Furthermore, adding to the amazement of the physical environment, the value of mirrors at the time made the project one of the most extravagant and exclusive of its era. Nothing like this interior had ever been created in Europe. Since then, the Hall of Mirrors has dazzled its visitors for centuries, and it is recognized as the most extraordinary achievement of classical eighteenth-century French Art (Figure 1).

The Hall of Mirrors was inaugurated in November 1684 and Colbert used this grand occasion to promote the Manufacture des Glaces. With such an impactful event, the company, which had troubled beginnings and had enormous debts, began to reach some financial balance, mostly with the increasing royal demands.[9] However, the company still had to fight for decades against the continuing contraband of Venetian glass into the country. Moreover, despite many restrictive measures implanted by Colbert in order to protect the royal company, it had to struggle with internal competition from the proliferation of small glassmaking manufacturers around the country. By then, the French production of glass and mirror was impacting the Venetian industry triggering a fifty percent reduction in price, making glass somewhat more affordable. However, mirrors were still extreme luxury items, not yet affordable to the masses, accessible only to the aristocratic class.

French Mirror Technological Innovations

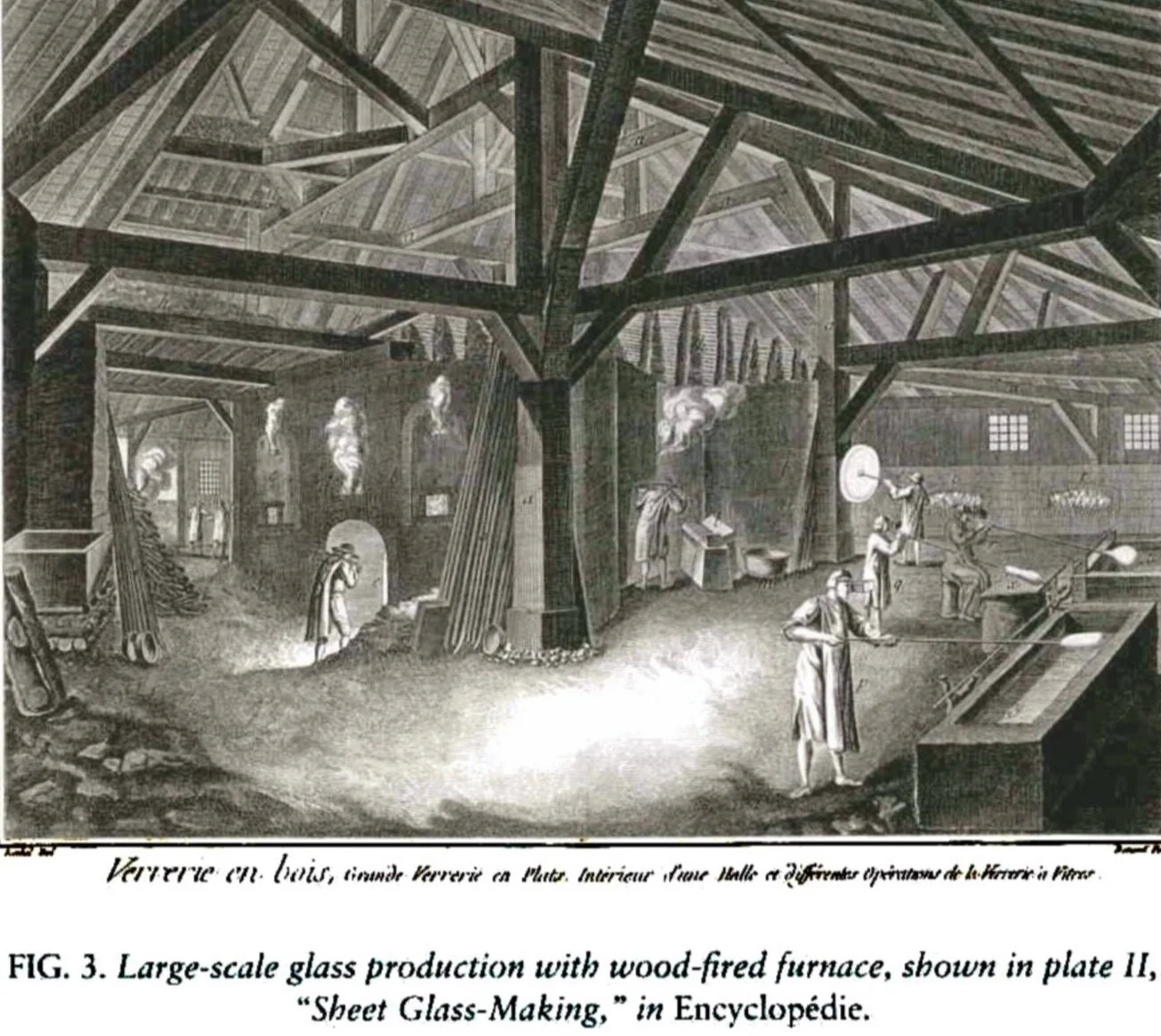

In 1680, some technical developments in the making of looking glass brought attention to France, diverting it from the Italian peninsula. An outstanding French artisan from Orléans, Bernard Perrot, devised an innovative technique of casting glass on a flat table, imitating the casting technique of metals (Figure 2). In kind, he was able to produce much larger pieces than were possible until then with blown glass (Figure 3). However, he could not obtain the necessary permits to commercialize his invention. In 1688, Thévart, director of Saint-Germain glasswork in Paris, utilizing the technique invented by Perrot, obtained the patent for its fabrication. Thévart had achieved manufacturing pieces measuring about five feet high. By Royal decree, he was granted permission to fabricate large mirrors but only if he manufactured pieces of glass that were more extensive than those produced by the royal company, which measured maximum sixty by forty inches.

Figure 2: Sheet Glass-making, 18th Century.

Figure 3: Large sheets of mirrors, 18th Century manufacturing

In this way, a rivalry was installed between the two companies: the original Manufacture des Glaces and the company owned by Thévart, Saint-Germain Glassworks, which were both operating under royal subsidies. After an investigation into the state of the finances of the two competitors, which concluded that they were both in poor financial condition, King Louis XIV decided to declare them bankrupt. He subsequently established a new glass company called the Manufacture Royale de Saint Gobain under a different governance and with which he obtained more successful commercial results than the previous ventures. Notably, the Manufacture Royale de Saint Gobain is still operating today.

By 1700 the Manufacture Royale de Saint Gobain was able to cast panes of glass measuring almost nine feet tall and more than three feet wide. Because of these technological advancements in France, a new cycle of defections and drama was unleashed, but this time, it was the French workers who were in high demand from England, Brandenburg, and Saxony. These events continued to attest how valued mirrors were in Europe during this period and to what extent the different countries and regions in Europe were willing to go to obtain the formulas for the most up-to-date qualities of mirrors.

It is important to note that during this period securing unblemished glass was very unusual. Even the highest-quality glass still showed “marbling, clouds, grease, rust, rusty or lead-darkened fibers, veins, “teardrops,” and muck. . .”[10] Nevertheless, this was the quality of mirrors that began to be used by the aristocracy in France at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The Impact of French Architecture

After the creation of the Hall of Mirrors, the role of French architects in incorporating mirrors as a common practice in the designs of palaces all over France became of leading importance, particularly in “hôtel particuliers,” mansions of the new burgeoning bourgeoisie that proliferated in Paris in the eighteenth century. Furthermore, the development of architecture in France was organized around some principles and rules of architectural execution devised by the the Royal Academy of Architecture, founded by Colbert in 1671. According to George Savage, the Academy “was charged with the duty of formulating the rules of architecture practice which had limiting and probably salutary effect on design, and of providing for the training of students.”[11] The Royal Academy of Architecture helped French architecture gain consistency and organization under common foundations. Its members became part of the most prominent figures in the design of noble and elite architecture and interiors.

Additionally, by the turn of the eighteenth century, the most notable architects began publishing treatises, building manuals, and collections of floor plans of the most distinguished innovations in architecture and interior decoration. During this time, architects were in charge of the design of the interiors, defining a new era of domestic architecture. Joan DeJean asserts that “they also edited compilations of striking examples of contemporary interior decoration, from the best ways to use mirrors to the most interesting new wall treatments.”[12]

Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the architect of the Hall of Mirrors, was also the designer of the most relevant architectural commissions of Louis XIV. He was assigned by the king of practically every relevant official project. In Versailles alone his works included in addition to the Hall of Mirrors, the North and South Wings, the Great and Small Stables, the Orangery, the Grand Commun, the Royal Chapel, the Groves of the Domes, the Colonnade Grove, the Grand Trianon, the Notre-Dame church and the Recollects Convent. He was named First Architect to the King in 1681, becoming Intendant in 1685, Inspector of Buildings in 1691, and finally Superintendent of Buildings in 1699, thus becoming one of the most authoritative architects of the era. It is through his influence that the French style was propagated throughout France and Europe. The greatest decorators (such as Jean Bérain and Pierre Le Pautre) and architects (such as Robert de Cotte, Ange-Jacques Gabriel, Germain Boffrand, Jean Aubert, Jean Courtonne and Pierre Cailleteaux) were all trained in his architectural studio, and it is through his disciples that his impact persisted.

After Hardouin-Mansart died in 1708, Robert de Cotte (1656 – 1735), who was particularly distinguished for his interior design, succeeded him as First Architect to the King. De Cotte was a close collaborator of Jules Hardouin-Mansart, completing the unfinished projects of his predecessor when he passed away.[13] He was made member of the Royal Academy of Architecture in 1699 and became director of the Academy in 1708, perpetuating Mansart’s legacy into the eighteenth century. He also created a number of works in western Germany along the Rhine, where the French style was favored. Among them, the Poppelsdorf Palace for the Elector of Cologne and his Electoral Palace in Bonn with a Cabinet des Glaces are relevant examples. The latter being an excellent instance of mirror application outside of France, implanting, in this way, the influence of the French style in the international arena. However, one of de Cotte’s most remarkable works was the design of the Galérie Dorée in the Hôtel de Vrillière (1714-1719), one of the three most lavish galleries built in France (along with the Hall of Mirrors and the Galérie d’Apollon at the Louvre). In it, he designed the finely-sculpted wood paneling with two trophies, one over the door with the triumph of Diane Chasseresse, and the other, a large mirror above the marble chimneypiece (Figure 4), with a sculpture of Leucothée, the protective goddess of sailors. The gilded mirror frame and “boiserie” on the walls and around ten pictorial frescoes, completed the decoration in the Regency style (1715-1723), a manner which became prominent after the death of Louis XVI. In addition, six mirrors were symmetrically displayed reflecting light coming through the large windows of the gallery.

Figure 4: Galerie Doree - Hotel Vrilliere

The Galérie Dorée is an exceptional example of how at the beginning of the eighteenth century it became established to incorporate mirrors over mantle pieces. Robert de Cotte is credited with the introduction of the palatial statement chimney mirror one encounters in so many architectural interiors of that period and on. Mirrors over the chimney-piece began to replace the paintings or the sculpted, carving or moldings made out of plaster, marble or stucco previously utilized in its place. At first, this novelty encountered some resistance to the new disorienting effects of mirrors which people were not accustomed to, but with time it became almost “de rigueur,”[14] and developed into a universal component in many palaces and mansions all over Europe and subsequently in countless interiors around the world.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, it had become a norm to renovate a room by remodeling the chimneypiece and placing a framed large mirror over it. If the room contained additional mirrors, the style of the frames would be consistent throughout the room, adding a special decoration above both the door and the top of the mirror. These ornaments could be made out of canvas, carved wood or drapery. The various motifs utilized included many alternatives and were relative to the style in vogue, but floral profusions, antique themes such as palms and scrolls, perfume-urns, and laurels were commonly used.

Figure 5: Le Petit Trianon - Versailles

Figure 6: Le Petit Trianon, Salon de Compagnie - Versailles

The architect Ange-Jacques Gabriel (1698-1782), member of the French Academy of Architecture, succeeded Robert de Cotte as First Architect to the King under the reign of Louis XV. Among his most distinguished works is the design of the Royal Opera House in Versailles and the Petit Trianon completed in 1768 for Madame de Pompadour whose façade and interior represent the emergence of the Neoclassical style in France (Figures 5 & 6). Multiple rooms in this small palace in Versailles had grand mirrors over the chimney mantels. Finally, Germain Boffrand (1667-1754) who also studied with Hardouin-Mansart, and who distinguished himself for having a unique style having been more influenced by Palladio and Louis Le Vau, designed one of the most exquisite examples of early rococo style: the Hôtel de Soubise (Figure 7). In the Salon de la Princesse, c. 1737, mirrors had a commanding presence. It is a circular room interlaced with large French windows, gilt “boiseries” and mirrors over mantel and furniture.[15]

Figure 7: Hôtel de Soubisse – Salon de la Princesse

The lineage of succession of architects starting from Mansart goes on, and by the beginning of the nineteenth century the incorporation of mirrors in multiple fashions had been established. This architectural language survived the challenging period of the French Revolution of 1789. When Napoleon came to power in 1802 and became emperor in 1804, the decorative arts had been impacted in a profound way, but a certain continuity remained in place. David R. McFadden asserts that “French primacy in the arts was firmly rooted in Pre-Revolutionary traditions and can, in fact, be traced back to the cultural policies of Louis XIV.” The use of mirrors in multiple ways was not challenged but rather perpetuated.

Referring to the Napoleonic period Eleanor P. DeLorme argues that “all the Bonapartes found select lodgings in or near Paris,”[16] which were decorated in a style evoking the Empire with motifs such as the imperial eagle, laurel leaves, griffins, stars and bees forged by Pierre François Léonard Fontaine and Charles Percier, the two architects of the Emperor. Josephine Bonaparte’s daughter, Hortense, moved into the Hôtel de Lannoy where there was a lavish reception room, the Salon de la Richesse, that had a design that was inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, with windows opening into the garden and mirrors in the opposite side. Moreover, Hortense’s boudoir in the Hotel de Lannoy had its walls covered with mirrors and surrounded by drapery; mirrors decorated the back wall of a niche with a divan, over the mantel and cabinetry (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Auguste Garnerey (French 1785-1824), The Boudoir of Queen Hortense, rue Cerutti, 1811. Watercolor, Olivier Lefuel Collection, Paris.

The Mirror Finish Application Evolution

While all over Europe the Louis XIV style was being emulated, after the death of Louis XVI in 1715, and under the Regent of the kingdom from 1715 to 1723, the focus on style, architecture and interiors moved from Versailles to Paris. Until about 1830 it was in Paris that the sumptuous interior architecture was been built and, as John Whitehead writes, “it was in the decoration of small, intimate, luxurious and harmonious interiors that the eighteenth century was to excel.”[17]

During the eighteenth century, the creative application of mirrors as interior finish in French architecture proliferated in numerous captivating ways. Mirror plates began being placed over doors, and large mirror panels were used to fill wall areas between windows. They were used “in paneling, in decorative frames, and even on ceilings for decoration or for the enlargement of spaces.”[18] They were allocated above console tables and commodes and sometimes they were surrounded by frames with candlesticks attached. Additionally, wall-sconces, multi-branched candleholders, and candelabra were incorporated into the interiors to enhance reflectivity at night, increasing the lighting particularities of the mirror’s reflections. It is also during the times of Louis XIV that the ceiling chandeliers with rock-crystal or glass drops began being incorporated to multiply the glittering effects of added reflections. For the same purpose girandoles, branched support for candles with crystal drops, were displayed on console tables, commodes, and wall shelves.[19]

Moreover, mirror rooms were created with doors, walls and sometimes ceilings lined with mirrors. The surface of the mirrors was occasionally topped with an ornament of carved gilt wood. Sliding mirror panels were also devised to cover windows and to hide fireplaces during the summer season. The mirror decorations were often grand, nearing ceiling height and in some cases the tops were finished with a painting, sculpture, or a piece of tapestry. Marie- Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI, the last Queen of France before the French Revolution, and an avid lover of luxurious interiors, had her bathroom lined with mirrors. The Dauphin, her eldest son, had his second antechamber at Versailles completely covered with mirrors including walls and ceiling. In it the mirrors were set in marquetry frames of ebony, tin and copper.[20] These are just two examples among an innumerable amount of interior spaces generated in the decorative arts of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries in France. Remarkably, the absolute majority of them, if not all of them had incorporated mirrors one way or another in their interior architecture.

Conclusion

Louis XIV’s finance minister Jean Baptiste Colbert and his vision of establishing mercantilist reforms, especially his system of taxation of imports and subsidies for domestic products generated a successful French industry of luxury goods for interior decoration, which for almost two centuries had no parallel. And mirrors were an integral part of that royal enterprise. In addition, Colbert’s founding of the Royal Academy of Architecture generated a synergy between the French industry and architects and designers, playing a major role first in the interior design of the Versailles Palace and subsequently in many royal palaces in and around Paris. Under Colbert’s purview, the Hall of Mirrors achieved its status as the most magnificent interior space of its time, which provided the template for imitation and determining palatial and aristocratic architecture throughout Europe long after his tenure and life.

On the other hand, the French architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart’s epiphany for the use of mirrors in the Hall of Mirrors triggered a myriad of developments and innovations in the decorative arts and interior architecture. The wonder of the material itself with its multiple effects in the interiors and in human beings concluded in an omnipresent use of the material.

Mirrors remain complex and fascinating objects capable of multiple functions. They can reproduce reality, represent the self, and can also generate a space between truth and illusion, and are capable of introducing an image within an image. They are beauty accessories and architectural and furniture finishes. Today mirrors, a common artifact, are everywhere and are central to every aspect of human life and culture. They are present in art, science, medicine, psychology, philosophy, technology, optics, and of course, architecture and interior design.

In contrast, in seventeenth century France mirrors were extremely rare and luxurious and the process of integrating them into everyday life was very distinct. The origins of the application of mirrors has a strong root in interior architecture. At first, mirrors provided a means to making the room seem larger and lighter by increasing interior reflections and giving the illusion of breadth to smaller rooms. Subsequently, the French discovery of the ample ways in which mirrors could be utilized is related to the fact that the mirror as a material is not comparable to any other architectural and decorative art finish. Its distinct capacity as a reflective surface, throwing back an exact image of the reality in front of it has had an enduring magical power over human imagination, and for this reason alone it stands out compellingly as compared to any other interior architecture and decorative art finish. It is also a surface that when used in medium to large sizes is very versatile and can be applied to an infinite number of interior styles since its inner surfaces remain mostly free of intervention and its outer edges are where different decorative designs can be applied. These traits guaranteed its permutations through time with evolving interior styles.

Furthermore, throughout Europe, mirrors became more and more favored, and they began to be used extensively in private and public places.[21] Through the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century, the architectural application of mirrors became more and more elaborate, transforming the landscape of French interiors from the time of the Hall of Mirrors onwards. Upon visiting Paris and the rest of France nowadays, it is observable in the overarching presence of mirrors in the interior landscape, whose precedents ascend to this period in French history.

The conceit of the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles led to Colbert’s measures to advance the manufacture of mirrors in France, which in turn generated technological advances in the country. Subsequently, Colbert’s instituting the academy of architecture generated cohesion in the field where mirrors had already been integrated in their interiors as a language. That language was then disseminated throughout Paris first, then France and Europe, and finally internationally, all over the world.

Notes

[1] Maurice Merlot-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception, trans. Carleton Dallery (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1964), 168-169.

[2] Sabine Melchior-Bonnet, The Mirror: A History (New York: Routledge, 2001), 58.

[3] Joyce O. Lowrie, Sightings: Mirrors in Texts - Texts in Mirrors, (New York: Rodopi, 2008).

[4] Joyce Lowrie, in her text titled “Sightings: Mirrors in Texts - Texts in Mirrors,” sums up these events this way: “. . . various workers had either been poisoned, or had committed suicide so as not to reveal their secrets. In despair, they had lost hope of ever returning to their country. They longed for Venice, or Murano, and their families, from whom they had been kidnapped. Colbert’s mastery in seducing Murano experts in mirror-making is called by DeJean, ‘a long-running soap-opera,’ given all the diplomatic as well as undiplomatic means that were used to extricate the secrets of mirror-making. . .”

[5] Lowrie, Sightings.

[6] Lowrie, Sightings, 119.

[7] Lowrie, Sightings, 119.

[8] George Savage Frederick, French Decorative Art 1638-1793 (New York: A. Praeger Publishers, 1969), 152-153.

[9] Melchior-Bonnet, The Mirror: A History, 48.

[10] Melchior-Bonnet, The Mirror: A History, 48.

[11] Frederick, French Decorative Art 1638-1793, 152-153.

[12] Clarissa Bremmer-David, Paris: Life & Luxury in the Eighteenth Century, (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011), 34.

[13] Frederick, French Decorative Art 1638-1793, 152-153.

[14] Pierre Verlet, Trans. George Savage, The Eighteenth Century in France: Society, Decoration, Furniture (Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company of Rutland, 1967), 92-93.

[15] Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 209.

[16] Eleanor P. DeLorme, Joséphine and the Arts of the Empire (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2005), 7.

[17] John Whiteread, The French Interior in the Eighteenth Century. (New York: Penguin Books USA, Inc., 1993), 11.

[18] Lowrie, Sightings.

[19] Frederick, French Decorative Art 1638-1793, 156.

[20] “The Dauphin and the Dauphine’s Apartments”, last modified May 31, 2019, http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/palace/dauphin-and-dauphine-apartments#the-dauphin’s-bedchamber

[21] Lowrie, Sightings.

Bibliography

Arminjon, Catherine, Yvonne Brunhammer, Madeleine Deschamps, France Grand, Raymond Guidot, François Mathey, David R. McFadden, Evelyne Possémé, Suzanne Tise. L’Art de Vivre: Decorative Arts and Design in France. New York: The Vendome Press, 1989.

Bremmer-David, Clarissa. Paris: Life & Luxury in the Eighteenth Century. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2011.

Chateau de Versailles. “The Dauphin and the Dauphine’s Apartments.” Last modified May 31, 2019. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/palace/dauphin-and-dauphine-apartments#the-dauphin’s-bedchamber.

DeLorme, Eleanor P., ed. Joséphine and the Arts of the Empire. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2005.

Graf Kalnein, Wend and Michael Levey. Art and Architecture of the Eighteenth Century in France. Victoria, Australia: Penguin Books, 1972.

Knothe, Florian. “Depictions of Glassmaking in Diderot’s Encyclopédie.” Journal of Glass Studies, 2009, 51, Design & Applied Arts Index (DAAI): 154.

Melchior-Bonnet, Sabine. The Mirror: A History. New York: Routledge, 2001.

Neuman, Robert. Robert de Cotte and the Perfection of Architecture in Eighteenth-Century France. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Roche Serge, Germain Courage and Pierre Devinoy. Mirrors. New York: Rizzoli, 1985.

Savage Frederick, George. French Decorative Art 1638-1793. New York: A. Praeger, Publishers, 1969.

Scott, Katie. The Rococo Interior. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Verlet, Pierre, trans. George Savage. The Eighteenth Century in France: Society, Decoration, Furniture. Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company of Rutland, 1967.

Walton, Guy. Louis XIV’s Versailles. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Whiteread, John. The French Interior in the Eighteenth Century. New York: Penguin Books USA, Inc., 1993.